On 20th November, 1975, fifty years ago last Thursday, Juan Carlos was proclaimed king and inherited absolute power, in accordance with the succession law established by General Franco, who had been the dictator of Spain since 1936. However, in a significant move, the king relinquished that power, paving the way for what the Spanish call “la Transición,” the transition to democracy. Last year, following devastating floods in Valencia, the Spanish Prime Minister, King Felipe, and his wife, Letizia, visited the affected area. They were met with hostile crowds who threw mud at them. While the Prime Minister legged it from the scene, the monarch and his wife stood their ground and engaged with the angry residents. Their unwavering presence earned them respect from many Spaniards who had previously been critical of the institution. Though far from perfect, the Spanish monarchy is seen by many commentators as a stabilising force in a country where trust in other institutions is in decline and its rancorous politics is alienating voters. Critics of any monarchy in modern Western democracies point out its antiquated raison d’être and argue that elected representatives serving as head of state is the right choice in the modern world. However, reality has often seemed to defeat that argument… The thing is, every form of government is inherently flawed because those who hold office are. It has always been the case, as illustrated by many biblical stories of hero-kings who became failed monarchs, such as David and his successor, Solomon.

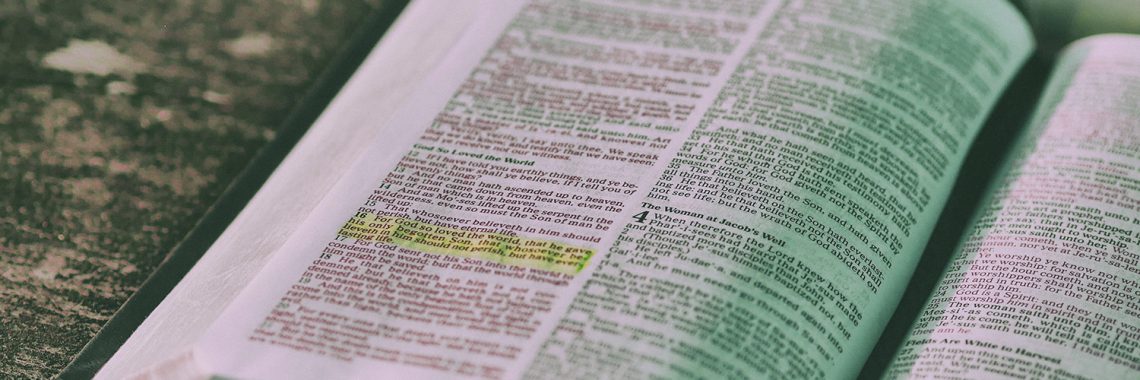

It’s essential to remember that when we refer to Jesus Christ as the King of the Universe, we should not interpret this title through our political perspectives or experiences. He made this distinction clear during His interrogation by the Roman governor Pontius Pilate: “My kingdom is not of this world. If my kingdom were of this world, my servants would have been fighting […]. But my kingdom is not from the world.” (John 18:36). It can be very tempting to use the Christian faith as a political ideology. Jesus faced a similar temptation when He was challenged by one of the criminals crucified alongside Him: “Are you not the Messiah? Save yourself and us!” This was the culmination of the crowd’s expectations and desires that had followed Jesus throughout His ministry. Until the moment of His crucifixion, He had consistently discouraged any attempts to portray Him as a political figure. Only while nailed to the cross, in a position of utter humiliation and powerlessness, did He reveal His kingship by exercising the most royal of powers: royal pardon, when He said to the condemned man beside Him, “Truly, I say to you, today you will be with me in paradise.” Paradoxically, the crucifixion scene underscored Jesus’ claim to the throne in the most understated way. His royal powers were unenforceable; they could only be effective when freely accepted: “Jesus, remember me when you come into your kingdom.”

The title we give to Jesus in today’s feast may seem outdated or even archaic. However, our political system of parliamentary monarchy can actually help us understand Jesus’ kingship. Constitutionally, the British monarch serves as the ceremonial head of state. Most of us can choose to ignore or even protest against this figure without fear of punishment, which was not always the case in the past. We can pay attention to the monarch’s words and actions, and ultimately, the choice is ours alone. Similarly, it’s up to each individual to decide what role Jesus plays in their life. He can be blanked out, as seems to be a default position for many. Alternatively, He can take on a ceremonial role during Christmas and Easter, serving as a convenient excuse for indulgence. However, Jesus can have a genuine and lasting positive impact on our lives when we allow Him to. We display crucifixes in our churches and homes to remind us that Jesus is the most benevolent ruler. While He may be proclaimed the King of the Universe, what truly matters is whether He is enthroned in our hearts.